Major new book about Hamilton Palace

The Virtual Hamilton Palace Trust is delighted to announce the publication of the long-awaited, two-volume book on Hamilton Palace, the Dukes of Hamilton and their collections by Dr Godfrey Evans, the Principal Curator of European Decorative Arts at National Museums Scotland and a Director of the VHPT.

Based on over forty years research, the eighteen chapters discuss the rise of the Hamiltons in the Middle Ages to Dukes of Hamilton and Brandon and Premier Peers of Scotland; the four Hamilton Palaces they created between 1530 and 1830; and what fifteen Dukes of Hamilton undertook and acquired. The most obvious and outstanding result was Scotland’s grandest private residence and its most important treasure house. The 445 illustrations include photographs of many of the rooms in Hamilton Palace, the best and most interesting works of art, and how items were grouped and displayed.

The book also explains why Scotland’s greatest collection was mostly sold off in the 1880s and 1919, and the enormous palace itself demolished in the 1920s.

ISBN 978 1 910682 49 4

832 pp (in two hardback

volumes, protected by a slipcase)

RRP £125.00, but

available from amazon books uk for £92.24, including free

delivery

The Trust

Formally launched at a reception in the Palace of Holyroodhouse on 3rd December 2003 by gracious permission of Her Majesty The Queen, The Virtual Hamilton Palace Trust has been formed to recreate the Palace in a virtual world on the Net and to reassemble as far as possible its unique collection of paintings, furniture and objets d'art which have been dispersed to become the treasures of museums around the world and to set these in their historical and cultural contexts through a series of research projects and the publication of related archive materials.

The Trust believes this would not only provide a hugely important resource for international scholarship, but that it would also have a direct and special significance for Scotland. Chatelherault is already a focus for tourism in Lanarkshire, yet it was merely the Palaces 'dog kennel', so to speak, a tiny structure in the Palace parks. The Trust believes people should have the opportunity of learning about the vast scale of the Palace itself, its galaxy of priceless treasures and those associated with it, both upstairs and downstairs. The Trust believes there is the potential for the project to become one of the most significant art/socio/historical research undertakings ever embarked upon in Scotland.

Rediscovering The Palace

"It is a thousand pities" wrote that doyen of departed country houses H. Avery Tipping in a preface to one of the 1919 Hamilton Palace sale catalogues, "that so great and historic a house should disappear. .. Within and without the Palace offers us of the best that the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries produced, and the present dispersal yields a very unusual opportunity of acquiring sumptuous examples of all three periods in the finest possible state of preservation."

The demolition of Hamilton Palace, then the principal residence of Scotland's premier Dukedom of Hamilton and Brandon, took place during the 1920s. Its contents, arguably the most magnificent ever assembled in this country, the Royal collections excepted, were dispersed through a series of sales beginning in the 1880s and culminating in 1919. There were, of course, good and particular reasons for the demolition of this great house and from to-day's vantage point we can also set the abandonment of such establishments more clearly in the context of changing economic, political and social conditions, but its destruction and the dispersal of its contents remain and will continue to be regarded as one of the greatest losses to national heritage ever to have happened in this country.

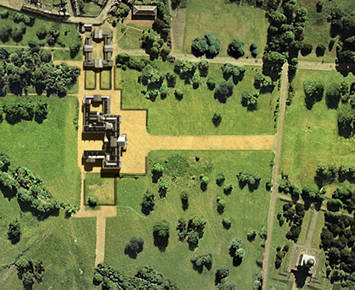

Virtual aerial view of landscape, 1896 (detail)

The image to the left shows a detail taken from the simulated aerial view, a re-creation of the estate landscape as it probably existed in the late 19th century and based on the 1:10,560 scale Ordnance Survey map of 1896. The image is interactive: mouseover the image to reveal the layout of the area as it appears on recent Ordnance Survey maps.

Hamilton and the Clyde valley

The site of what was once Scotland's largest and most magnificent country house, replete with the country's greatest-ever private collection of art treasures, is today occupied by a modern commercial retail park and road system dating from the 1990s, just to the west of the M74, Scotland's busiest motorway. The sheer contrast in style and setting between the palace complex which developed over the centuries and what now exists in Hamilton Low Parks could not be greater. This contrast provides a special challenge to re-create this one-time treasure-house and its parklands from old photographs, drawings and manuscripts, and especially from images of its priceless collections which have found their way around the world.

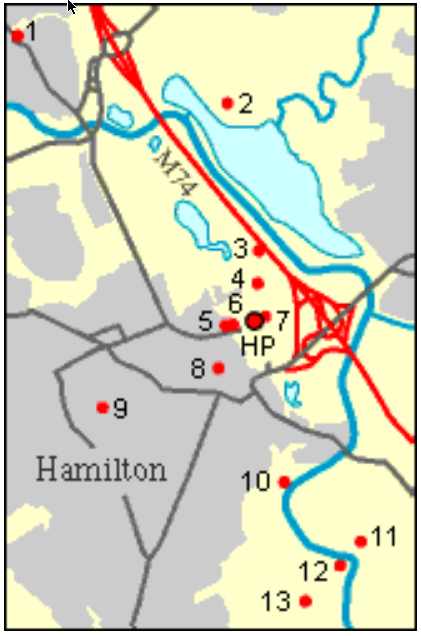

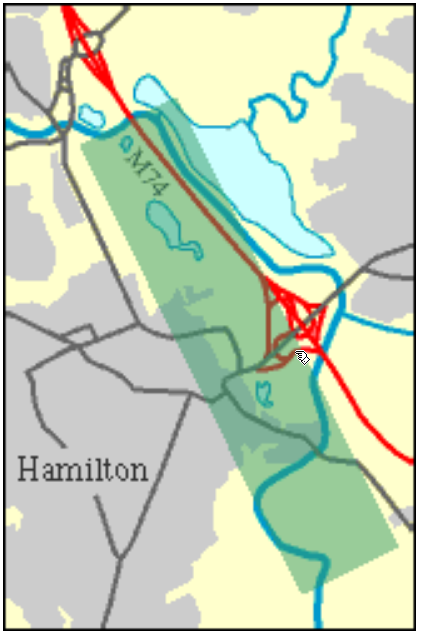

This pair of maps shows, in the context of modern Hamilton and the complex configuration of roads in this part of the Clyde valley, the former location of Hamilton Palace and its many associated local properties.

The maps above are reproduced from Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office © Crown copyright 2003. Any unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. RCAHMS GD03135G0011.2003

The site of the palace itself (HP) is at the centre of the map on the left, occupying a favoured position on the fertile river plain. On the right, the same map is used to show, against a modern background of roads and built-up areas, the strip which forms a simulated 'aerial' view of the estate landscape as it probably existed in the late 19th century.

Reading from north to south on the left-hand map, the other buildings and monuments which have an association with the history of the palace, and which for the most part appear on this website, are as follows: 1. Bothwell Parish Church; 2. Hamilton Palace Colliery (site); 3. Nethertoun Motte; 4. Hamilton Mausoleum; 5. Hamilton Museum; 6. Riding School; 7. Collegiate Church (site); 8. Hamilton Old Parish Church; 9. Bent Cemetery; 10. Barncluith; 11. Châtelherault; 12. Cadzow Castle; and 13. Hamilton High Parks.

Background Movie Clip: the 10th Duke and Hamilton Palace

Paul Murton: “Alexander the 10th Duke was a very flamboyant character. He set about making the already magnificent Hamilton Palace even more opulent.”

Rosalind Marshall: “He was tremendously proud of his own family, and his own position, and this connection with the Royal Family. He really wanted to make this the most grandiose house in Scotland, so that people could see exactly how important the Hamiltons were.”

PM: “But the Duke’s Grand Design didn’t come cheap. Alexander wanted Hamilton Palace to have the equivalent of a Royal Collection. This was a task he threw himself into with great enthusiasm, travelling the world, seeking out rare and exotic pieces of art. It’s said that during his lifetime he spent the equivalent of hundreds of millions of pounds, amassing an incredible collection of paintings, sculpture and furniture. The Duke’s collection contained a number of now world-famous paintings. But he had one particular obsession: Napoleon. He even went to the extent of commissioning what has become one of the most iconic portraits of the Emperor – when Britain was still at war with France.

RM: “I wouldn’t be surprised if his obsession with Napoleon was in a way a reflection of his own view of himself in the world – they were both flamboyant characters who were projecting their personalities. Perhaps he felt an affinity…

PM: Alexander’s art collection at Hamilton Palace would have dwarfed the likes of the famous Burrell Collection. Sadly, it is now spread to the four winds, auctioned off to pay family debts. But even more tragic was the fate that befell the building that had housed his magnificent collection. This is the site of Hamilton Palace. Now for us today it is hard to believe the fate of this once vast and imposing building. But the Hamiltons were once heavily involved in the mining industry. Unfortunately, they undermined the foundations of the Palace itself, and in the early nineteen hundreds it began to subside badly. And in 1921 it had to be completely demolished. So today, the once grand house of the Hamiltons has become this sports centre and a retail park.

Interviewee Dr Rosalind Marshall Presenter Paul Murton Producer Kathryn Ross Last broadcast on Mon, 2 Nov 2009, 20:00 on BBC Two (Scotland only).

Video extract courtesy of BBC Scotland and Mentorn Media, from "Clan Hamilton - Grand Designs" (Scotland's Clans Series)

Background Movie Clip: Tour of the Palace

A virtual hamilton house tour of the house and the family that built it, here is a brief presentation by one of today's most distinguished scholars and researchers, Dr Godfrey Evens. Godfrey is the Principal Curator of European Decorative Arts at the National Mueseum, and a Director of VHPT.